by Dr Hans Christoph Atzpodien, Managing Director of Bundesverband Deutscher Sicherheits- und Verteidigungsindustrie (BDSV), and Lucas Hirsch, Sustainability Analyst at BDSV, Berlin

It was in Paris in 2015 when 196 nations approved a joint commitment (Paris Agreement) to limit global warming to 1.5C and to reach carbon neutrality in the second half of this century at the latest. Among the EU Member States, this commitment took shape in the so-called “Green Deal”. The declared goals were to reduce emissions, create new jobs and improve the wellbeing of European citizens. Since then, this “green” grand strategy is gradually being implemented through an increasing number of EU directives, thereby establishing a vast number of tools to turn the intangible notion of sustainability into something tangible and measurable. The defence industry is treated like any other industry in Europe and consequently, manufacturers of defence equipment for governmental security branches will be measured and categorised according to the same Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria as every other industrial activity conducted inside the EU.

Defence vs sustainability?

We in no way intend to call for special treatment of the security and defence industry in the form of an exemption from upcoming directives on due diligence in the supply chain and the like. Nevertheless, we see a problem in the fact that, regardless of the sustainability performance of the companies in this industry, many in the financial markets often see these companies as incompatible with ESG criteria, simply because they produce armaments, even if it is for EU and NATO forces.

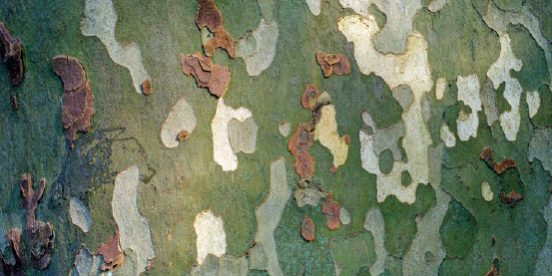

Our following considerations are therefore a strong plea for an “Olive-Green Deal” to be attached to the “Green Deal”, in order to create explicit EU standards for harmonising Green-Deal expectations with NATO and European defence policy objectives and requirements. The aim is to provide guidance to financial markets and eliminate the supposed contradiction between security and defence in Europe and sustainability.

ESG criteria have already gained considerable importance in financial markets and the trend is rapidly continuing. The fact that they have already reached the highest levels of financial market governance is demonstrated by the association of 114 central banks and supervisory authorities to form the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). In the context of the Green Deal, the European Central Bank (ECB) has also formulated specific expectations for banks on how to consider these risks within their business models and strategies, their governance and risk management models, as well as on disclosures. Simultaneously, the ECB is intending to give preferential treatment to green bonds. Rather unsurprisingly therefore, financial markets are not exactly characterised by their positive approach to the industry.

Lack of general regulatory guidance

While “controversial weapons”, banned by international treaties, are quite naturally to be excluded, the true problem begins where financial markets set general exclusions based on percentage thresholds of turnover in the armaments sector, regardless of the purpose for which these products are ultimately intended and who the customer is. Thresholds between 5% and 25% of revenue are most common and can be derived from either legislation or investor industry associations. The EU Ecolabel for Retail Financial Products, i.e. retail funds but also savings accounts, which is currently being drafted, provides for the exclusion of companies with more than 5% of their turnover in armaments. In the absence of general regulatory guidance on how different kinds of products and industries are to be handled in this era of sustainability disclosures, financial market actors tend to establish their own guidelines. Several German investment funds and banks for instance have jointly developed a market standard under the Level 2 amendments to MiFID, effectively excluding companies that derive more than 10% of their turnover from production or distribution of military hardware. The problem is that a definition of what precisely “military hardware” is, has not been proposed.

The Ukraine war – a turning point?

Ever since the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the idea has finally established itself among the governments of the EU Member States that efforts to arm the European component of NATO ought to be massively increased. This is especially true for Germany, which so far has failed to fulfil its NATO pledge to spend at least 2% of its annual GDP on defence. Moreover, it is now abundantly clear that war is, in essence, the absence of sustainability values as set out in Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The brutal war unleashed on Ukraine by Russia deprives people of their fundamental social rights, including the right to adequate food, water, sanitation, clothing, housing and medical care. In addition, Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states unambiguously that every human being has the right to life, liberty and security of person. We see a broad consensus among NATO member states that armaments, under the NATO rules of engagement, are the prerequisite for our ability to maintain peace and security in our part of the world. The conclusion that must be drawn from this is bindingly obvious: NATO armaments and weapons are the very basis for sustainability in our countries, both from an environmental and a social point of view.

Therefore, in order to establish an understanding that can influence the decisions of private actors, especially on financial markets, a solid regulatory “bridge” is needed between the Green Deal on the one hand and the urgent need to increase armament expenditure for NATO’s European arm on the other. We call this bridge an “Olive-Green Deal” which we are proposing as a supplementary chapter to the Green Deal. The responsibility for building such a “bridge” rests with those EU Member States who are also NATO members, as it is NATO that defines the concrete requirements for the military capabilities needed to fulfil NATO’s overall mission.

The pros and cons of “green” military equipment

The question is to what extent military equipment must be “green” in order to meet the overall societal goals set out in the Green Deal? At the same time, to what extent must exceptions be made so that armed forces are able to fulfil their tasks? Interestingly, the issue of “green defence” can be looked at from different perspectives. For instance, soldiers have an operational advantage if, for example, they can fight with a decentralised supply of renewable energy, such as a fuel cell, in their backpacks. In this case, green technology applications serve a dual purpose: they enhance capabilities and provide environmental benefits at the same time. In other cases, however, the application of green technologies impedes military capabilities. If, for example, all military vehicles were required to be electrified, in line with the planned civilian standards in the EU, this would significantly limit their range in most conflicts.

NATO has already carefully thought out and elaborated defence scenarios, on the basis of which its required military capabilities are to be conceived. This is exactly the kind of background into which both options and limitations of green technologies for NATO armed forces should be embedded. What is ultimately needed is a set of NATO-defined “green” technological requirements as well as exceptions. It follows therefore that there must be clear-cut parameters on the extent to which military technology ought to be green and the extent to which it cannot be green, to guarantee operational effectiveness. Such exemptions would need to be included in any EU directive that contains sustainability related obligations or requirements.