by Cyrille Schott, Préfet de Region (h), and Board Member of EuroDefénse-France, Strasbourg

Joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in different postures, from the beginning France and Germany did not have the same approach to NATO, the military organisation of the Transatlantic Alliance, and this continues today.

Diverging approaches from the beginning

France signed the North Atlantic Treaty on 4 April 1949 and thus belonged to the founding members of the Atlantic Alliance. It actively contributed, notably at the Lisbon Conference in 1952, to the politico-military structuring of the alliance, NATO. It hosted NATO’s headquarters in Paris. It was not, however, in direct contact with Soviet-dominated Europe. Being a permanent member of the UN Security Council, it was also a power with global interests, still in possession of a colonial empire.

The Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) acceded to the North Atlantic Treaty in 1955, following the Paris Agreement of 1954. Faced with the Soviet danger, this accession responded to the American will for German rearmament and came after the failure of the European Defence Community on 30 August 1954. For Chancellor Adenauer, rearmament and NATO membership meant the return of sovereignty to Germany, the loser of the war. The Paris Agreement put an end to the occupation regime and recognised “the full authority of a sovereign state” to the FRG; the Three Powers (France, UK and the US) nevertheless retaining their rights regarding Germany as a whole until the reunification.

Two armies with a different relation to NATO

The West German Army was built as a NATO army, under the direct command of NATO and, until the end of the cold war, without a General Staff of its own. The FRG has also undertaken not to manufacture any atomic, chemical, or biological weapons. This army, under the tight control of parliament (Bundestag), was on the front line against the Warsaw Pact armies and had no military involvement elsewhere. NATO, with the presence of American troops, appeared to be a fundamental guarantee of security of Western Germany.

While its forces stationed and integrated into NATO, the French army, under national command, deployed largely outside the European continent and fought wars in Indochina (1946-1954) and then in Algeria (1954-1962). It often clashed with the anti-colonialism of the United States, with the Suez crisis in 1956 marking profound differences.

1966 – a first caesura in NATO’s history

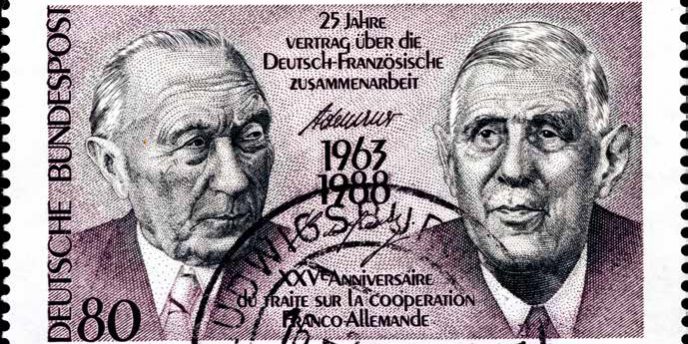

Although it ended the Algerian war in 1962, after having given independence to the African colonies in 1960, President Charles de Gaulle’s France, through its overseas departments and territories, remained present in a large part of the globe and kept bases in Africa, where it did not hesitate to launch military operations. It also asserted its own position in international affairs. Against the will of the United States, it built an independent nuclear force. When the 1963 Elysée Treaty, the founding act of Franco-German friendship, was ratified in the Bundestag, the latter accompanied it by a preamble affirming the close ties of Germany with the United States and NATO.

In March 1966, de Gaulle announced that France was withdrawing from NATO’s integrated military structure, while remaining a member of the Atlantic Alliance. Allied forces, especially American forces, left France. NATO headquarters were relocated to Belgium. However, various agreements, including the Ailleret-Lemnitzer Agreement of 1967, ensured the close link of the French forces in Germany with NATO. Subsequently, relations between France and NATO were normalised. In the Euromissile crisis, President Mitterrand spoke out in favour of NATO’s deployment of Pershing II missiles in Germany, in response to the Soviet SS 20 missiles, and gave his support to Chancellor Kohl in his speech to the Bundestag in January 1983.

France and Germany in post-cold war NATO

Closeness and nuances

At the end of the cold war, NATO turned to new horizons. It became involved in the former Yugoslavia, led an air operation against Serbia in 1999 during the Kosovo crisis and then, far from European territory, engaged with the United States in Afghanistan after the terrorist attacks of September 2001. France and Germany participated in the actions against Serbia and in Afghanistan but refused to follow the Americans in the Iraqi adventure in 2003 (without NATO involvement), whereas Germany did not follow France and the United Kingdom in the NATO-led operation against Libya in 2011. Depending on its assessment of the appropriateness of these interventions, the decision was made independently by each of the two countries, and, except for Libya, they agreed.

France reintegrating NATO

In 2009, under President Nicolas Sarkozy, France reintegrated NATO. The latter, enlarged towards the east following the Soviet collapse, regained its raison d’être after the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and especially after the Russian aggression against Ukraine in 2022: the defence of democratic Europe. Whereas Germany, a central European power, has been participating in NATO’s “forward presence” in the Baltic countries and Poland since 2017, leading one of the four multinational battlegroups (that of Lithuania); France, especially engaged in the Sahel against the jihadist threat, contributed more modestly.

Strategic autonomy vs transatlantic fidelity

Germany and France adopted a common position in support of Ukraine. Germany became its main European arms supplier and decided to deploy a brigade of 4,000 men in Lithuania. France took the lead of one of NATO’s four new battlegroups, in Romania, where it holds 1,350 soldiers on site. France keeps other commitments around the world; Germany, as a major power in Europe, reaffirms its vocation in continental defence. And it is designing it within the framework of the Atlantic Alliance, together with the United States. While acknowledging NATO’s and the US’ role, France has defended the idea of Europe’s strategic autonomy for years, which was met with scepticism by Germany and other European countries seeing the distrust of NATO and the potential weakening of the American guarantee. When President Macron spoke of NATO’s “brain death” in 2019 in the Economist, referring to the impossibility of coordination between the US and its allies in the face of Türkiye’s aggressive actions, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas immediately replied that NATO was Europe’s “life insurance”.

Closeness beyond the couple’s quarrels

The war in Ukraine has shown that NATO and the United States are indispensable in the defence of the continent. But after the Trump presidency, the awareness of this has increased: EU Member States, Germany included, need to urgently build their own defence. However, at the same time, Germany sees France retaining a certain reluctance towards NATO and not appreciating the true value of its contribution to the defence of Europe, while France continues to find Germany still too dependent on the Americans and NATO for this European defence.

Because of their history, their geographical location, the way they situate themselves in the world, Germany and France do not have an identical approach to NATO. However, it should not be forgotten that, beyond their couple quarrels, they have developed a closeness that is rare in history and are both leading partners of the Atlantic Alliance.

Cyrille Schott

is a retired French regional prefect. After graduating from the National Administration School (ENA), he was an advisor to the office of French President Mitterrand from 1982 to 1987. Thereafter he started his prefectural career in Belfort, followed by five appointments as a departmental prefect and two as a regional prefect. After his appointment as a Chief Auditor in the Cour des comptes (audit office), he ended his career as the director of the National Institute for Advanced Security and Justice Studies (INHESJ). He is a reserve colonel and a board member of Eurodéfense-France.